We saw significant increases in life expectancy during the 19th and 20th centuries, thanks to healthier diets, medical advances, and many other improvements in quality of life.

But after nearly doubling over the course of the 20th century, the rate of increase has slowed dramatically in the past three decades, according to a new study from the University of Illinois Chicago.

The analysis found that despite repeated advances in medicine and public health, life expectancy at birth among the world's longest-living populations has only increased by an average of six and a half years since 1990. This rate of improvement is far less than some scientists expect Life expectancy will rise at a rapid pace in this century, and most people born today will live more than a hundred years.

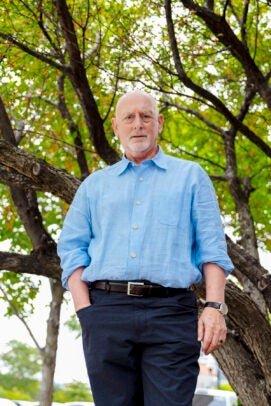

The Nature Aging paper, “The Impossibility of Radically Extending Human Life in the 21st Century,” provides new evidence that humans are approaching the biological limit of life. Lead author S. Jay Olshansky of the California International University School of Public Health says the greatest increases in longevity have actually occurred through successful disease control efforts. This makes the harmful effects of aging the main obstacle to further expansion.

“Most people living to advanced ages today are living in the time that medicine created,” said Olshansky, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics. “But these medical dressings produce fewer years of life even though they occur at an accelerating pace, meaning that a period of rapid increases in life expectancy has now been documented.”

This also means that extending life expectancy further by reducing disease could be harmful, Olshansky added, if those extra years are not healthy years. “We must now shift our focus to efforts that slow aging and prolong health,” he said. Healthspan is a relatively new metric that measures the number of years a person has been healthy, not just alive.

The analysis, conducted with researchers from the Universities of Hawaii, Harvard and the University of California, is the latest chapter in a three-decade debate about the possible limits to human longevity.

In 1990, Olshansky published a paper in the journal Science in which he argued that humans were approaching the maximum life expectancy of about 85 years, and that the most significant gains had already been achieved. Others predicted that advances in medicine and public health would accelerate twentieth-century trends into the twenty-first century.

Thirty-four years later, evidence from the 2024 Natural Aging Study supports the idea that life expectancy gains will continue to slow as more people are exposed to the harmful and irreversible effects of aging. The study looked at data from the eight longest-living countries and Hong Kong, as well as the United States – one of the few countries that saw a decline in life expectancy in the period studied.

“Our finding overturns the conventional wisdom that natural longevity for our species exists somewhere on the horizon ahead of us — a life expectancy that exceeds what we have today,” Olshansky said. “Instead, it is behind us – somewhere in the range of 30 to 60 years. We have now demonstrated that modern medicine achieves progressively smaller improvements in longevity even though medical progress is occurring at an astonishing speed.

Olshansky said that while more people may reach 100 or more in this century, these conditions will remain extremes and will not raise life expectancy significantly.

This finding is at odds with products and industries, such as insurance and wealth management companies, that increasingly make their calculations based on the assumption that most people will live to be 100.

“This is very bad advice because only a small percentage of the population will live this long in this century,” Olshansky said.

He said the results do not rule out that medicine and science can produce further benefits. The authors say there may be more compelling potential to improve quality of life at older ages than to prolong life. More investment should be made in gerontology, the biology of aging, which may hold the seeds of the next wave of health and life extension.

“This is a glass ceiling, not a brick wall,” Olshansky said. “There is a lot of room for improvement: to reduce risk factors, work to eliminate disparities, and encourage people to adopt healthier lifestyles – all of which can enable people to live longer and healthier. We can push back this glass ceiling on health and longevity through science.” Aging and efforts to slow the effects of aging.