A polarized nation heads toward one of the most important presidential elections in years.

It is the conflict abroad that is driving protests across the country.

The current president is backing his vice president after he was ousted by his party ahead of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

The Democratic National Convention, which begins later this month at the United Center, shares some striking similarities to the infamous 1968 edition. But the 2024 edition will struggle to be etched in memory and history the way those violent few days 56 years ago did, leaving a stain on Chicago’s reputation.

Mayor Richard J. Daley unleashed the Chicago police on antiwar protesters to demonstrate his brand of law and order—a decision that backfired, damaging the Democratic Party and its political machine. Republican Richard Nixon was elected president that November.

But the 1968 conference helped change public opinion about the Vietnam War and the draft, highlighted the need for police reform, prompted journalists to reconsider their trust in government sources, and ushered in a new era of social and political activism.

Here are some stories from the 1968 conference from people who were there.

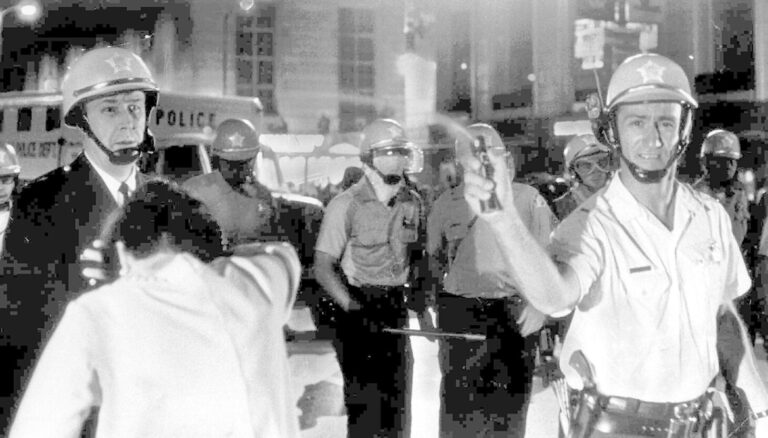

Police lead a protester out of Grant Park during demonstrations that disrupted the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in August 1968.

“You opened my eyes”

Don Johnson, a young Newsweek reporter, was covering the second night of protests downtown when a Chicago police officer approached him and struck him twice in the knee with a baton. The night before, he recalls, he saw a colleague taken to the hospital after a baton-wielding cop struck him in the ribs.

“He just did his training, and this was not police behavior,” Johnson says.

As a national audience watched on television the mostly young white protesters being beaten by officers, views of police brutality began to change, Johnson says, even though black activists had long warned of police violence.

“These were white, middle-class kids — suburban boys and girls,” says Johnson, 84. “It opened people’s eyes.”

He says it also led journalists to become more skeptical of what government officials were telling them, such as Daley's denial that he ordered police to attack protesters.

How did the police see it?

Eyes were opened on both sides of the protest lines.

Then-Chicago Police Officer Bob Angone, 84, who was pulled from his tactical duty on the South Side to help patrol protests in Lincoln Park, says it was immediately clear how unprepared the police were for a week of demonstrations.

“Nobody knew who was who. It was just a tangled mess with very little leadership. The cops were on their own, breaking ranks, in chaos,” Angoni says of seeing fellow officers smash the skulls of protesters, some of whom rained rocks, dirt and urine-filled balloons on the cops.

Angoni recalls that the chaos broke out at 11pm on the first night of the protests.

“The parks close at 11 o’clock, and now we have thousands of people who have come to Chicago and have nowhere to go,” said Angon, a retired police lieutenant who now lives in Austin, Texas. “There’s no supervisor there. It was us against 10,000 to 15,000 people. We weren’t safe, and they weren’t safe either.”

Protesters regroup near the Hilton Hotel on Michigan Avenue after being chased out of Grant Park with tear gas on August 29, 1968.

The violence continued until sunrise each day, with police chasing and beating protesters throughout the area.

“They were beaten when they left and beaten when they tried to stay,” says Anggun, who was then in his third year as a policeman.

He says he would go back to his parents' house on the city's south side to get a few hours of sleep, then return to the front lines to work 16-hour days with little food except bologna sandwiches provided by Daly's Democratic organization in the 11th Ward.

The National Guard—mostly made up of troops with no knowledge of police work—didn’t help, nor did Daley’s infamous directives earlier in the year to “shoot to kill arsonists” and “shoot to maim looters” during the riots sparked by the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. that year.

“I saw a 10-year-old kid running past me with a gumball machine. I was supposed to shoot him, and that shows you the kind of leadership we had,” says Angon, who did not follow that directive. “Chicago would have had its own Nuremberg trials if the cops had followed Daley’s orders and shot and killed people.”

New doubts

In Chicago, the deep skepticism the agreement generated led to the creation of the Chicago Journalism Review and a new focus on reporting on government corruption, misinformation, and issues of racial and social justice.

A little over a year later, the raid and shooting of Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton in Chicago by law enforcement officers raised many questions about the official version of the incident.

The scenes, broadcast on national television and published in newspapers across the country, influenced opinions about police conduct, government and the Vietnam War, said Don Rose, 93, a lifelong Chicagoan who served as an adviser to the king. It was Rose who coined the phrase “the whole world is watching,” which could be heard repeated many times during the Chicago police crackdowns.

“Complaints from the black community were often ignored,” says Rose, who advised King during his efforts to desegregate housing in Chicago. “It helped the white world realize that police brutality was real.”

Images of police violence changed opinions not only about war and police, but also about the political machine that Daly led.

“When they cleared the park, they beat up a lot of people,” Rose says.

The anti-war message resonated widely with the national public after the conference, Rose says:

“It definitely helped get the project done.”

He says the convention also spurred the emergence of the “Lakefront Liberals,” voters who elected the likes of William Singer and Dick Simpson, Chicago City Council members who challenged and began to roll back the power of the Chicago political machine, and helped elect Mayor Harold Washington in 1983 and 1987.

National Guard is not ready

Gordon Quinn, now 82, a University of Chicago graduate and war-dissident filmmaker, remembers tear gas being released on Lake Shore Drive as he headed to his Lincoln Park apartment. When he got there, he saw National Guardsmen stationed on the roof of his building.

He said he saw guards in the city centre pointing their guns at a mother who was driving near the barricades hoping to pick up her teenage children from a protest to take them home.

“There's the National Guard there, and they're not trained for this kind of event,” Quinn says.

Two years ago, Quinn founded Kartemquin Films, now known for its decades-long social justice films, including the 1994 documentary “Hoop Dreams.”

Quinn recalls 1968 and says what happened at the time led to a surge in political activism: “It radicalized a lot of people and helped them understand that they couldn’t stand the lies of the government.”

Police try to divert protesters as they attempt to clear Grant Park during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on August 28, 1968. One protester has fallen to the left while another can be seen on the ground to the right, while others gather in the foreground.

Janet Kloss had recently graduated from Northeastern Illinois University when she and a few friends headed downtown from the west side to take in the scenic views.

“It was my first experience of a serious, large-scale protest,” says Kloss, now 77, a retired Chicago Public Schools teacher. “I was staying back because I didn’t want my parents to see me on TV.”

She says tear gas filled the air above Grant Park, where “people were being beaten and thrown into carts.” “We were basically protesting the Vietnam War, and it was like we were participating in it,” she says.

Kloss says she and her friends only stayed downtown for a few hours as tensions mounted.

“It just kept piling up,” she says. “The more the police didn’t know what to do, the more frustrated they got, and they thought, ‘If we can kill people, we’ll bring the numbers down.’”

This only underscores the importance of the protests, according to Kloss, who says from her perspective: “If this is happening here, what is happening to the people over there?”

Michael Klonsky, 81, who was national secretary of the activist group Students for a Democratic Society, said the events that followed the conference were a “decisive moment for the protest movement.”

Klonsky says he believes the activity surrounding this year's Democratic caucus will be similar in many ways.

He points to campus protests over the war between Israel and Hamas, saying elite schools across the country have seen protests much like those seen during the Vietnam War years.

“I don’t protest anymore,” Klonsky says. “I’m too old and too slow. But I understand those students who are sacrificing their privileges.”

Nixon ended the draft, believing that doing so might curb some of the protests against the war.

“The draft made foreign policy and war-making personal,” says Bill Ayers, a former activist with Students for a Democratic Society. “Politicians and the Pentagon learned something: Don’t draft. It’s very good that we abolished the draft, but it was a cynical move.”

The events of 1968 were a defeat for the Democrats. Nixon was elected president and re-elected before resigning over the Watergate scandal.

“I and others were blamed for Nixon's election,” Klonsky says. “That was certainly not our intention.”