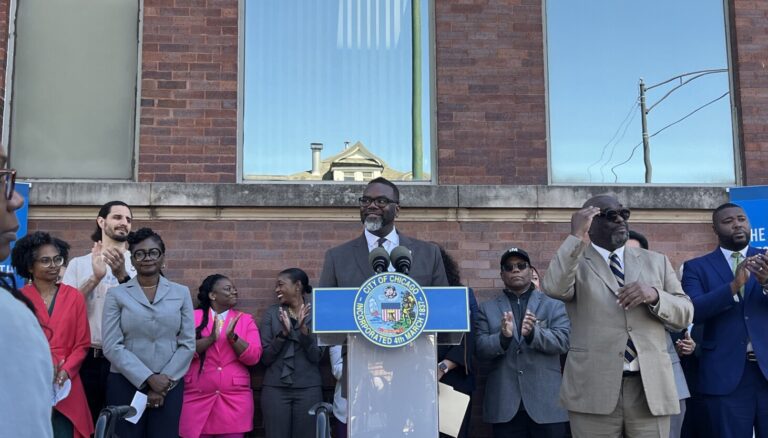

Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson on Thursday unveiled long-awaited plans to expand public access to mental health care in Chicago and reopen a shuttered clinic in the city, a promise he made during his campaign.

This year, the city plans to reopen the Roseland Mental Health Clinic and add mental health services at the city's Pilsen clinic and at the Legler Regional Library in West Garfield Park. These neighborhoods were chosen based on need, and the city says Legler is one of the busiest distribution sites for the overdose-reversing Narcan nasal spray.

Johnson wrote in a report from a working group that was examining how “mental health is not just a personal issue: it is a collective concern that touches every corner of our society, from our homes to our schools, our workplaces, and beyond.” To expand mental health services in Chicago.

Johnson often spoke of his brother Leon, who he said died a drug addict and homeless. He cited his brother's name again Thursday as he pledged that the city “prioritizes those left behind and ignored by previous administrations.”

“Our city has gone from 19 mental health centers to just five. We have begun to rely more heavily on our police and fire departments to respond to behavioral health crises. But that trend is ending,” Johnson said, standing in front of the red brick building that once housed the Roseland Clinic. Today,” he later added: “I will continue to keep my brother Leon front and center.”

The city also wants to phase out the use of police in responding to mental health crises. Instead, it wants to double the number of so-called CARE Alternative Response Teams, where paramedics and mental health workers go out on calls. The goal is to de-escalate someone with a mental health issue and connect them to the medical care they need without police involvement.

Mental health advocates who have pushed the city to reopen clinics for years were emotional as they reflected on the long-awaited reopening. I give birth. Rosana Rodriguez Sanchez, Ward 33 and lead sponsor of the Treat Not Trauma campaign, said advocates “fought like hell” after being “told 'no' too many times.”

“I want to thank the mayor for keeping his promises,” said Diane Adams, a longtime advocate for public mental health clinics who participated in the cordon off the Woodlawn clinic to protest its closing. “I'm someone who came out of the system. Look at me now. I'm a strong woman now.”

The working group was formed last fall to study how to expand public mental health. Advocates, including the Community Wellness Collaborative, have documented the shortage of mental health providers across the city and how that trickles down to people who need help, such as long wait times to see a provider. They have pushed for Chicago to reopen city-run mental health clinics that were closed under former Mayor Rahm Emanuel more than a decade ago. Today there are five.

Emanuel's successor, Lori Lightfoot, has taken a different approach, expanding access to mental health care by investing in dozens of private and nonprofit health clinics that already provide it. A study conducted by the cooperative last year still found barriers to receiving care at some health centers.

Johnson pledged to reopen mental health clinics in the city. In his first year, he launched an assessment of the city's mental health landscape and unceremoniously fired Lightfoot's health commissioner, Dr. Allison Arwady, who had championed the use of private, nonprofit providers to expand access for Chicagoans. In his first budget, Johnson included funding to reopen two clinics and expand the reach of CARE teams.

Asked whether the city would stop using private, nonprofit providers to fund the expansion of public services, Johnson Public Health Commissioner Dr. Simbo Ige said: “We are using all our options, because the need is huge.”

These providers are often the backbone of health care in low-income communities.

More than 65% of Black and Latino Chicagoans experiencing serious psychological distress receive no treatment, according to the Chicago Department of Public Health. While whites made up the highest rates of Chicago residents who died by suicide from 2018 to 2022, there was an uptick among older adults and Black residents in particular.

There are nearly 40 recommendations from the working group that serve as a roadmap for expanding access to mental health. They generally include adding more services, improving and expanding the response to non-police behavioral and mental health crises, and enhancing community awareness of available mental health resources.

In recent hearings on what Chicagoans want for mental health care, a majority did not know the city had free mental health clinics, according to the collaborative.

Looking ahead, the working group recommends that the city prioritize access to 24/7 services, and that the government establish metrics to track and evaluate mental health expansion.

The group also acknowledged that reopening more mental health centers is not always the answer despite the harm it may cause to people and communities. There may be different models of care that can be explored.

“Simply put, what worked in 2012 may not work today,” the report said, referring to the year Emanuel closed half of the city’s 12 mental health clinics.

In its report, the working group highlights a number of challenges. The city is competing with hospitals, private practices and other organizations amid a shortage of mental health workers and is already struggling to fill vacant positions, though the report also says the public health department has hired enough doctors to staff the three new mental health sites this year. year. The city has already hired 19 therapists, Ige said.

The group recommends the city build a community care authority to staff clinics and CARE teams with not only providers but also case managers and peer support workers.

“It is important that the Corps include careers that do not require advanced degrees and are accessible to individuals with lived experience,” the report said.

The city's public health department had nearly 500 job openings last year, making up just over 40% of its positions. Beniamino Capilupo, of the city's human resources department, said the government has worked to make wages more competitive, boost hiring and post job openings more quickly, including posting the emergency medical technician role that will be part of the expanded program.

“The fact of the matter is we have a lot of vacancies and we have a lot of vacancies,” Capilupo said. “But we need our recruiters to get out, so we encourage recruiters to actually get out of the community and go to career fairs.”

Other challenges include how expensive it is to maintain and expand mental health services, especially as pandemic relief funds run out. While the city has provided medical care at its clinics for years, responding to the behavioral health crisis is relatively new for Chicago, the report said.

Johnson's plan is expected to cost about $21 million this year, which is already included in the mayor's budget. By 2027, these costs are expected to rise to $37 million. The working group estimates there will be a funding gap of about $20 million that year.

Rodriguez Sanchez said the dream would be to “reopen them all” and create a city-run mental health center in each ward.

“I know this is very ambitious… but this is how we win,” she said. “We have big dreams and we have big ambitions, and then we slowly start to realize those dreams and take steps toward what we actually want to see.”

The city's clinics have been underutilized in the past, and when asked if the cost was worth the investment, Johnson insisted: “Any investment we make to provide mental health services to families is a worthwhile investment.”

Kristen Schorsch covers public health and Cook County government for WBEZ. Tessa Weinberg covers city government and politics for WBEZ.